Between the quarantine memes, I’ve seen quite a few people share that they have picked up gardening, urban or otherwise, as a hobby while in home isolation. Funny, cuz I bought a plant at my pre-quarantine Trader Joe’s run and it immediately died.

Anyway.

This brought to mind a fascinating piece of medieval monastic heritage that I examined in a paper for a Sustainable Agriculture course I took to senior year (in true humanities major fashion, to fulfill a science requirement). A somewhat idealized monastery blueprint, the Plan of St. Gall (link includes analysis and transcription of the entire thing, you can zoom in, it’s really amazing) is a ninth century manuscript which details the minutiae of a monastery property including multiple gardens–one for vegetables by the hencoop (pictured) and one for herbs, by the infirmary.

These small details, along with a host of other hints at daily monastic life to be found in the plan and its attached key, give us a fascinating glimpse as to the daily habits, both liturgical and mundane, of a typical Carolingine community of Benedictine monks. However, what I find even more fascinating, is the revelatory role of this document: so very little has changed about monastic culture over the centuries, one can find almost identical monastic communities even in the United States today.

Most of the vegetables and herbs labeled in the rows of the garden plans are still useful and edible plants today–many part of the eternal herbal canon in St. Hildegard of Bingen’s phyisca, composed couple centuries after Gozbert drafted the Plan in Switzerland. Hildegard’s work illuminates a special synergy between plants and the religious communities they fed–gardening, in effect a form of prayerful manual labor prescribed by the Rule of St. Benedict, serves a unique purpose as it stewards the earth for the sustenance of God’s children.

The Monastery Garden Cookbook, one of several culinary masterpieces by a French monk at a monastery in New York, is a piece of the same tradition we witness in the Plan of St. Gall. In the introduction to this book, Brother Victor-Antoine d’Avila-Latourrette (one hopes he goes by “Brother Victor” colloquially) expounds on how gardening has been intertwined with the monastic tradition all the way back to the famed hermit St. Antony, the “father of all monks.” His frugal recipes, immortalized in writing much like Hildegard’s herbal remedies, perpetuate a centuries-old legacy of sustainable garden-to-refectory food. To learn more about Brother Victor’s horticultural habits, this reflection by the man himself is a must-read.

This is all just to say that if you are considering picking up gardening in these times when we should all stay at home, I cannot recommend a better inspiration for a small, sustainable garden than the tradition of monastery gardening that has lasted at least 1200 years and counting. If you lean toward the herbal rather than the edible, instructions for a “Hildegarden” can be found here.

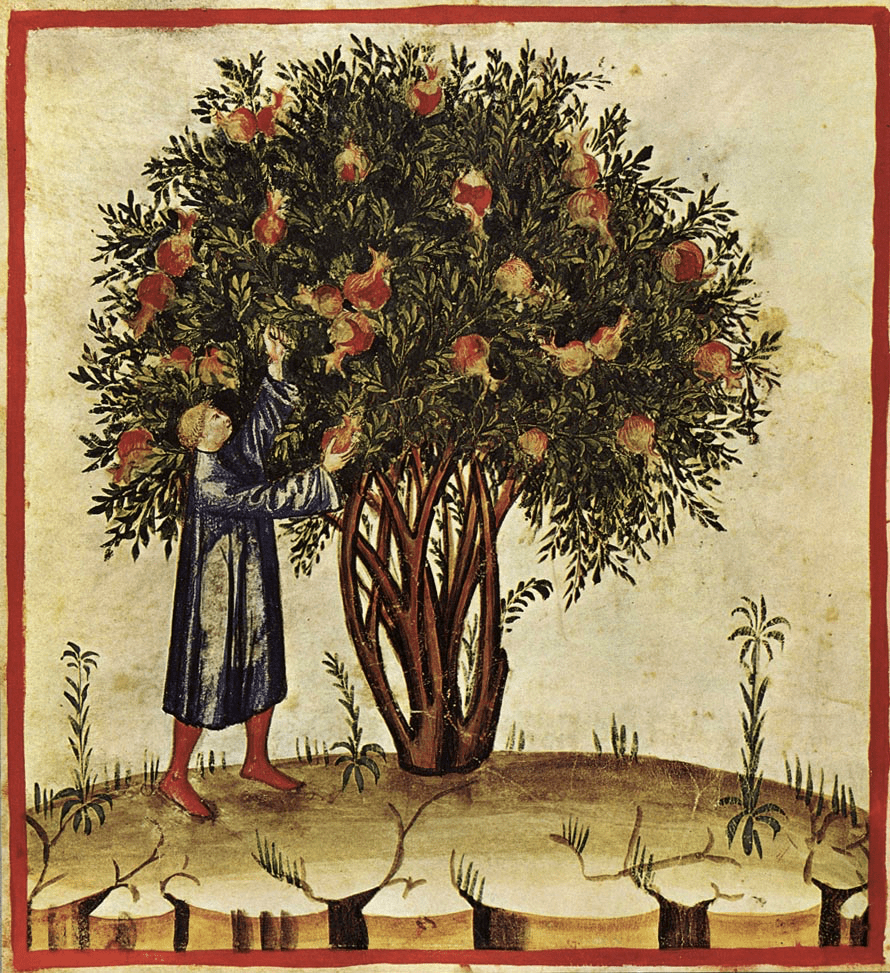

I could wax eloquent about how monasteries have so well maintained God’s command of having “dominion over the earth” through careful, prayerful stewardship and frugality, but I will leave you with a delightful gardening image from the Tacuinum Sanitatis, a popular medieval Latin translation of an Arab health handbook that included ample information about good eating and herbal remedies, much like Hildegard’s Physica. You can read a fancy scientific study about it here and view a detailed summary of the Tacuinum and its content here.